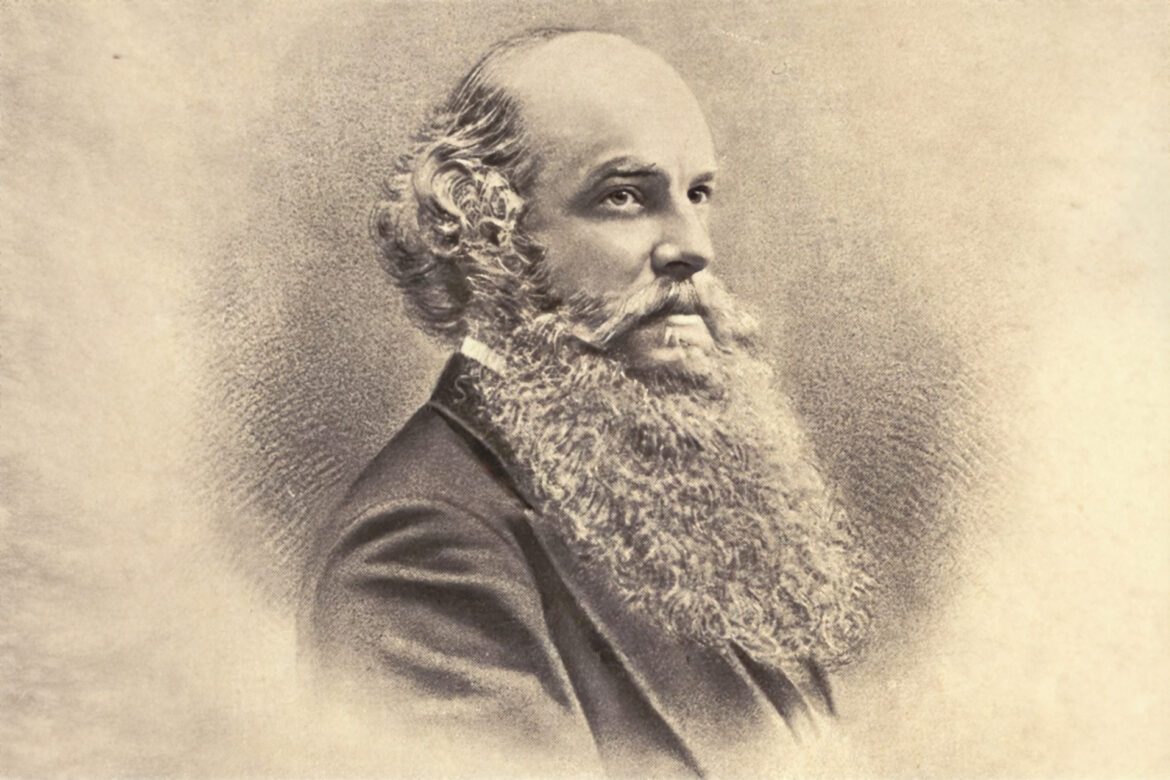

Lawrence Oliphant (August 3, 1829 – December 23, 1888), a British author, traveler, and diplomat, born in South Africa, embraced Christian Zionist thought.

Oliphant was a member of the United Kingdom Parliament for Stirlingburgh, and was also a British intelligence agent.

His satirical novel “Piccadilly” – which he published in 1870 – is the most famous book of his life, and he later rose to prominence through his plan to establish the first Jewish agricultural communities in modern-day Jerusalem, known as the “Gilead Land Plan.”

His birth and upbringing

Lawrence Oliphant was born in Cape Town Colony, South Africa, on August 3, 1829, the only child of Sir Anthony Oliphant (1793-1859), who was a member of the Scottish nobility, and his wife, Maria, who were also Christian Zionists.

At the time of his son’s birth, Sir Anthony was Attorney-General of the Cape Town Colony, and was soon appointed Chief Justice of Sri Lanka, where Lawrence spent his early childhood in its capital, Colombo.

The credit goes to Sir Anthony Oliphant and his son brought tea to Sri Lanka and planted 30 plants brought from China in the Nuwara Eliya region, where the family lived.

In 1848 and 1849, he and his parents toured Europe, and in 1851 he accompanied Jung Bahadur from Colombo to Nepal, and this trip provided him with rich material to write his first book, “A Journey to Kathmandu” (1852).

Lawrence Oliphant returned to Ceylon (the old name of Sri Lanka), and from there he went to England to study law, after which he left his legal studies and traveled to Russia, and the result of that tour was his book “The Russian Shores of the Black Sea” (1853).

Diplomatic and spiritual life

In 1861, Oliphant was appointed First Secretary of the British Legation in Japan, and in 1863 he was sent to Poland as a British observer to report on what was known there as the “January Uprising.”

He returned to England, resigned from the diplomatic service, and was elected to Parliament in 1865 for Stirlingburgh, although he did not show any clear ability to practice parliamentary work.

He achieved great success thanks to his satirical novel “Piccadilly” (1870), and then he came into contact with the spiritualist Thomas Lake Harris, who in 1861 organized a small utopian Christian community called the “Brotherhood of New Life” in the Brockton area on Lake Erie near New York, and then moved to Santa Rosa in California.

After a period of refusal, in 1867 he was finally allowed to join the society founded by Harris, and Oliphant caused a scandal by leaving Parliament in 1868 to follow Harris to Brockton.

He lived there for several years engaged in what Harris called “use”, manual labor intended to advance his utopian vision, as members of the community were allowed to return to the outside world from time to time to earn money.

Three years later, Oliphant worked as a correspondent for the British newspaper The Times during the Franco-German War, after which he spent several years in Paris serving the newspaper. There, through his mother, he met his future wife, Alice Le Strange, and they married in London on June 8, 1872.

Later, he and his mother fell out with Harris and demanded their money back, which was allegedly derived mainly from the sale of her jewelry. This forced Harris to sell the Brockton colony, and his remaining disciples moved to their new colony in Santa Rosa, California.

Gilead’s plan

By 1878, in the midst of a wave of Western anxiety about Russia’s intention to invade the Middle East, Oliphant devised the so-called “Gilead Plan,” under which Britain established a Jewish agricultural colony in the northern, more fertile half of Palestine, with the approval of pro-Zionist British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli and Minister The then foreign minister, Robert Cecil, Marquis of Salisbury, the Prince of Wales, and the British novelist Mary Anne Evans, known by her pseudonym George Eliot.

In his book “The Land of Gilead” – which he wrote in 1880 during the Ottoman rule – Oliphant put forward proposals to settle Jews in the region and develop it economically and politically in order to strengthen the Ottoman Empire and make it a barrier to the Russian encroachment into the Middle East.

The book includes maps of the proposed railway system from Ismailia to Haifa via the Dead Sea, Jerusalem and Tiberias with a branch line to Damascus, and Oliphant’s vision predicted trade and pilgrimage between neighboring countries and residential development outside the major cities.

The proposed line from Beirut to Jaffa, which connects with the Ismailia line via Haifa and the Palestinian coastal plain, has already been built, and part of the Haifa to Tiberias line has also been built.

Accredited by the British government, Oliphant sailed in 1879 to investigate the terms of establishing a Jewish agricultural settlement in Palestine, and later saw Jewish agricultural settlements as a means of alleviating the suffering of Jews in Eastern Europe.

In May 1879, Oliphant went to Constantinople (now Istanbul) to submit a petition to the Sublime Porte (Ottoman rule) for permission to establish a Jewish agricultural colony in the Holy Land and settle large numbers of Jews there, and this was before the first wave of Jewish settlement by the Zionists. In 1882.

He did not see this task as impossible due to the large numbers of Christians in the United States and England who supported this plan, and with financial support from the Christadelphians (a Christian religious group) and others in Britain, Oliphant collected sufficient funding to purchase land and settle Jewish refugees in Galilee.

While awaiting an appointment with the Sublime Porte, Oliphant traveled to Romania to discuss proposed agricultural settlements with the Jewish communities there. The long-awaited meeting finally took place in April 1880, but it was a miserable failure, as Oliphant and his plan were rejected.

In the opinion of Henry Layard, the British ambassador to the Sublime Porte at the time of Oliphant’s visit, the efforts failed, because Oliphant spoke of the return of the Jews to Palestine as bringing about the second coming of Jesus, a language and ideas that Sultan Abdul Hamid II found unacceptable.

When a wave of pogroms swept the Russian Empire in 1881 – most notably the Kiev pogrom – charitable funds were raised in London under the auspices of the Palace Committee, and when the committee announced that the funds would be used to help Jewish refugees settle in America, Oliphant published an article in the Times on February 15. 1881 in which he affirmed that the Jews who chose to settle in Palestine would enjoy the protection of their religion.

Loyal to the Jews

His article was met with such enthusiasm among Polish and Russian Jews that the Palace Committee appointed him Commissioner of Galicia (Galicia) in Spain.

In 1882 Oliphant and his wife Alice traveled to Vienna and Galicia, met with representatives of Eastern Jews and promised that “as soon as Christian sympathizers in England are convinced that Jews fleeing Russia can settle safely in ‘the land of their ancestors’ they will contribute hundreds of thousands of pounds to the promotion of this great object.”

At this point, Oliphant had become a celebrity among Jews in Eastern Europe, and was spoken of as a savior and as “another Cyrus” (Cyrus, a Persian king who gathered the Jewish diaspora and their homeland in Jerusalem).

His settlement plans were published in the early Zionist newspaper Hamaged, written by Peretz Smolenskine in Hashahar, and Moses Lilienblum expressed his hope that Oliphant would be “the Messiah of Israel.”

According to historian Nathan Michael Gelber, “In the homes of poor Jews you could find a portrait of Oliphant, and it would be hung next to portraits of great philanthropists like Moses Montefiore and Baron Hirsch.”

Despite the fact that the Sublime Porte had not granted any permission for the construction of Jewish agricultural settlements, in May 1882 the Oliphant family began a journey to Palestine, traveling via Budapest to Moldova, stopping there to meet Rabbi Avrohom Yaakov Friedman, whom Oliphant understood to be a “Jewish leader.” The World” hoping to convince him to raise enough money to buy Palestine from the Ottoman Sultan.

The Oliphants settled in Palestine, dividing their time between a house in the German colony of Haifa, and another in the Druze village of Daliyat al-Carmel on Mount Carmel, and Naftali Hertz-Imber, Oliphant’s secretary, the author of the Israeli national anthem “Hatikvah,” lived with them.

Lawrence and his wife Alice collaborated on an esoteric Christian mystical work in 1885, influenced by the American mystic Thomas Lake Harris and the spiritualists Anna Kingsford and Edward Maitland.

In December 1885 Alice became ill and died on 2 January 1886. In 1888 Oliphant traveled to the United States and married his second wife, Rosamund, granddaughter of Robert Owen, in Malvern.

Death

The couple planned to return to Haifa, but Oliphant fell ill at York House in Twickenham, England, and died there on December 23, 1888.

His obituary in the Times said: “There has rarely been a profession more romantic or full of detail, and perhaps never will he have had such a strange or contradictory character.”

After the declaration of the establishment of Israel in 1948, many streets were named after Oliphant, in the upscale Palestinian neighborhood of Talbiyah, whose residents were displaced, in Haifa, the German neighborhood where Oliphant lived, and in Safed, northern Palestine.

In 2000 Alice Oliphant’s watercolors showing Haifa as it was in the late 19th century were displayed in a special exhibition entitled “Mrs. Oliphant’s Drawing Room” at the Israeli National Maritime Museum.