Marrakech – At a time when the Arab screen shrinks about dealing with crucial issues, the presence of Al -Quds Al -Sharif in Moroccan cinema comes to devote a reality facing many challenges.

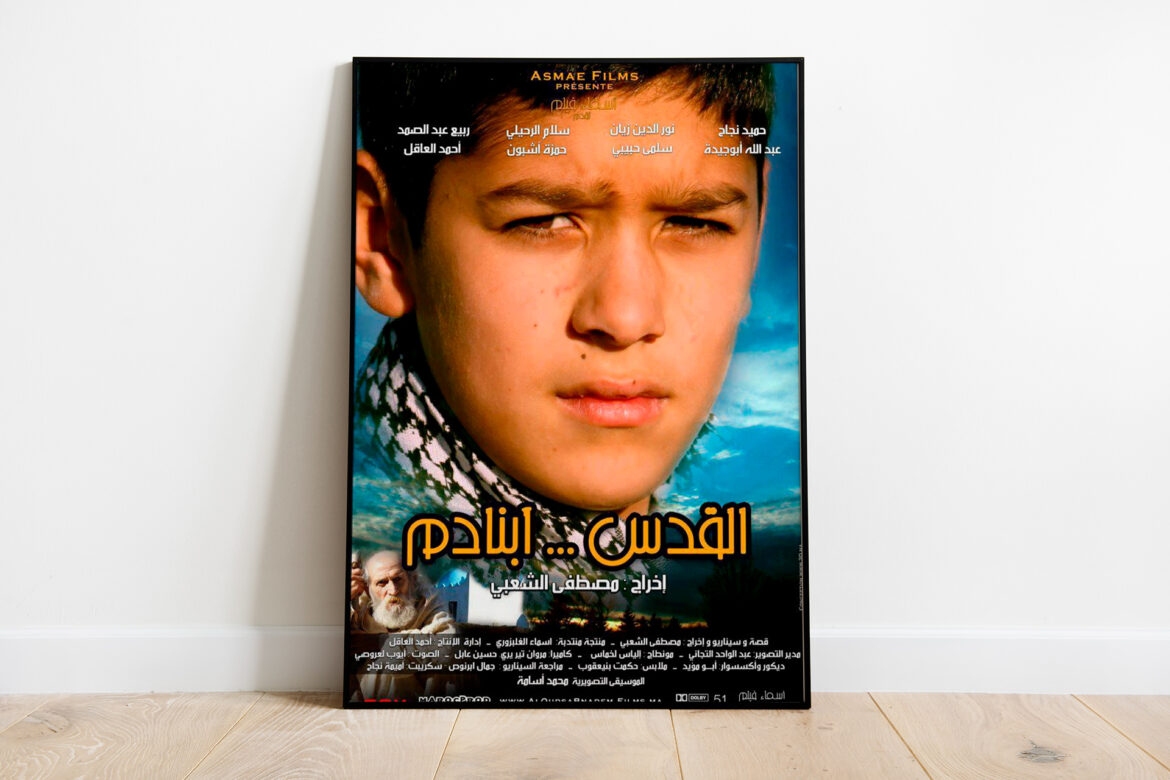

In Morocco, the local cinema produced only three films that dealt with the Holy City directly, one of which is short and a novelist is “Jerusalem, Abnadam” by Mustafa Al -Shaabi, and the second and the third documentary entitled “Al -Aqsa Yusq Al -Aqsa” by Abdel Rahman Lawan, and “Al -Quds Bab al -Mughrabi” by the late Abdullah Al -Misbahi.

It seems that it is not only a limited number of titles, but a creative experience that places Jerusalem in the heart of Moroccan preoccupation that goes beyond the political or religious dimension, to be carried out to memory and conscience.

The return to eating these films comes in the context of a very sensitive Moroccan popular awareness towards Palestine and Jerusalem, to ask the most important question, how did the image express a place far away spatially, and symbolically close? How is the Holy City evokes in a Moroccan cinematic space? This is the bet that the three directors fought, each in his own way.

“He chose to work on the symbol through a youthful story related to football, while the documentary films were involved in stabilizing the facts and memory.”

He adds, “The importance of films lies in their integration, as the novelist feels, and the documentary is convinced, and both of them devote the symbolism of Jerusalem a living issue in Moroccan consciousness.”

Emotional idea

The cinema is not only a tool of acting, but it is often an expression of an internal question, this is what the director Abdel Rahman Luoan expressed as he recalls the beginnings of his documentary project.

“I have this question in conjunction with my interest in cinematic directing, what is the secret behind the Moroccans’ connection with the land of Palestine and their issues and they are the most distant Arab peoples west of them?” This question turned into an idea, the idea into a movie, and the film into an experienced experience.

As for Mustafa al -Shaabi, the director of “Jerusalem, Abnadam”, he started from a different feeling, stemming from a feeling of symbolic oppression and lethality.

In a published interview, he says that the film worked on “the state of jealousy that moves the neighborhood’s boys when they discover our shirts carrying the phrase Jerusalem, the capital of the entity, and they attack it with stones.”

It is not just a symbolic snapshot, but an expression of the instinct of the inherent resistance even in the people of the Moroccan popular neighborhoods.

While Izz al -Din Shallah, head of the Jerusalem International Festival, to Al -Jazeera Net, confirms that such cinematic initiatives need a strong personal motive, “The problem is that this type of motivation is always not always available, especially when the scenario or director is not in direct contact with the reality of the city.”

But it seems that the Moroccan conscience, with its high symbolism, creates this seam from afar.

Language and symbol

When the ability to photograph inside Jerusalem is absent, the avatar is attended by a creative alternative. Al -Shaabi chose in his movie “Jerusalem, Abnamm” to turn a stadium into a front, and a shot into a speech.

The critic Mustafa Al -Talib believes that the strength of the film lies in his employment of the symbol, as “the boys hit the team with the occupation’s spices with stones”, in a scene that summarizes the uprising in a shot, and makes the Moroccan child similar to the Palestinian stones.

“The title of the film itself stores a warning force,” Abnadam “in the Moroccan dialect is an appeal and a coexistence, it is Jerusalem, beware, do not be unaware of it, here it is not a direct message to a message, but rather to stimulate the awareness of the audience through a familiar scenery in the Moroccan context (football) in order to carry it towards a greater question.

On the other hand, he talks to Awan about the privacy of the cinematic language in the documentary tape, “What distinguishes the strength of the documentary is its intensification of data, meanings and facts that the individual may not find enough to read it in references.”

“In this sense, the image becomes a means of intense reduction, and it carries a historical and cultural content that is transmitted without theoretical.”

Antilation of awareness

Language in the three films is not subject to pure aesthetic technology, but rather serves a deeper goal, improving awareness, and moving the symbolic inhabitant towards a city that steals in every news scene.

The storytelling in “Jerusalem, Abnadam” takes a symbolic imaginative character, while the documentary depends on strict documentation, this contrast does not reflect a variation in cinematic power, but rather a diversity in the tools of influence.

“The short film worked on the symbol, while the documentary highlighted the role of the tape in dealing with fateful issues by diving into collective memory,” says Mustafa Al -Talib.

He added, “In the popular movie, the story is built through almost silent scenes, in which the act speaks, not the dialogue.

As for Awan, he relied on an archive and testimonies of Dr. Abdul Hadi Tazi, Saeed Al -Hassan and others.

“I have witnessed the data of the tape spoken by young men, intellectuals and preachers after they were limited to circulation,” says Awan.

Here the documentary turns into a channel to transfer memory from the elite to the audience, and from the text to the image.

The feature film and the documentary film, despite their difference in their structure, meet at one point, and the reformulation of the story of Jerusalem with a Moroccan tongue, expressing a real emotional engagement in a distant conflict geographically, but it is symbolic and culturally close.

Story of the Avatar

How can Jerusalem evoke in a Moroccan movie? The answer may be visual, mental, or both. In “Jerusalem, Abnadam”, the Holy City never appears, but every scene contains a symbol or resonance. The neighborhood stadium becomes a resistance yard, the shirts are a letter tool, and the stones are an extension of the memory of the uprising.

The student believes that this indirect work serves the idea more than simulating reality, because the avatar has the power of suggestion that compensates for the absence of the actual site. The film does not depict Jerusalem, but it makes it attend an appeal and a provocation of the spectator’s awareness.

On the other hand, Al -Misbahi and Awan chose to evoke Jerusalem through testimonies and documentary scenes, the first through photography in Jerusalem, and the second relied on an archive, interviews and clips from inside Morocco.

“Morocco embraces the Jerusalem Committee and the House of Money of Jerusalem, and the existence of the door of the Moroccans, all indications that made me see that Jerusalem lives in Moroccan consciousness, and if I did not actually visit it,” says Awan to Al -Jazeera Net. The film proves that the place may not be a condition for filming, as long as the live space is memory and the situation.

In this sense, Jerusalem in Moroccan cinema becomes an internal space more than geographically, which is called through history symbols and testimonies, and it is reshaped on the screen visually from inside Moroccan neighborhoods.

A bet worth it

To accomplish a film on Jerusalem from Morocco not only an artistic challenge, but a productive adventure fraught with obstacles.

“The issuance of the license from the Moroccan Film Center was not easy, which indicates the importance of the defined cinematic works.” This was not the last obstacle, but the documentary later found a wide resonance in festivals and institutions, which proved that the bet was worthy.

As for the critic Mustafa Al -Talib, he believes that the weak capabilities did not prevent the people from creating a strong symbolic film, “If it had great capabilities, the film would have been stronger, but he was able to recall the issue.”

This is reflected in the broader Arab reality, as Izz al -Din Shallah says, “Self -production requires a marketing plan, and government support is almost non -existent. Unfortunately, there is not enough interest that makes the Jerusalem issue a priority in financing films.”

Jerusalem is absent from the cinema, not because the directors do not care, but because the cinematic industry does not put it among its priorities.

And between the absence of support and the difficulty of marketing, films such as “Jerusalem, Abnadam” and “Al -Aqsa lives in Al -Aqsa” remain a noble exception, and an individual voice in collective silence.