Gaza is the home of war, diaspora, departure, and death, a space for diaries narrated by its writers, writers, and witnesses of the war, so realistic that it does not need imagination or imagination for the recipient to continue reading it and following its chapters.

It is a “raw” novel whose heroes, characters, and narrators are real, flesh and blood. Do not read it to sleep because its characters will haunt you in your dreams, and the water you drink will become salt. Drinking water has become scarce in Gaza, and people will drink salt tomorrow, and your body will overcome you and you cannot answer the call of nature. You get tired walking with the displaced people under aircraft bombardment and soldiers’ orders to search for a safe place, clinging to a life in the midst of war.

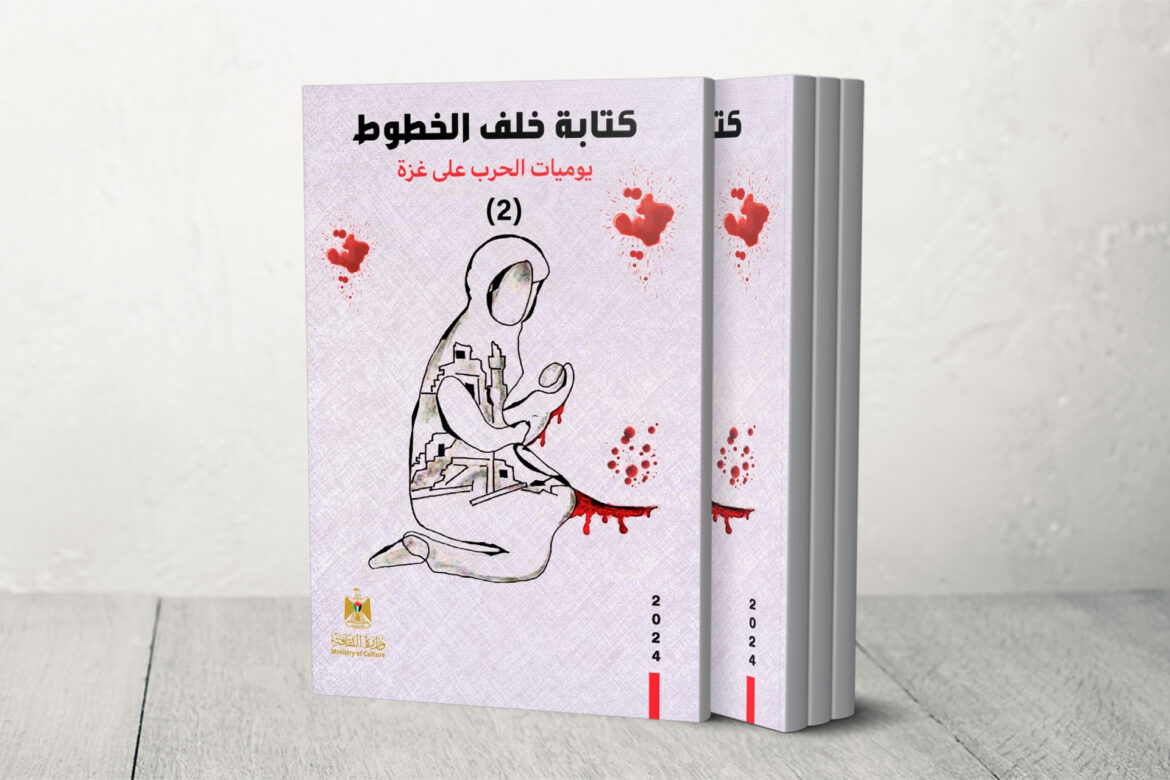

It is a war that will end – according to the presenter of the book “War Diaries in Gaza… Writing Behind the Lines,” the former Palestinian Minister of Culture, novelist Atef Abu Saif, “and people will return to their homes and rebuild the valley that witnessed their departure, and they will embrace those they left on the rubble of homes.”

According to Abu Saif, these diaries issued by the Palestinian Ministry of Culture “are not a book about Gaza, but rather about the people, the place, and life there during the war that targeted its existence.”

From Siti’s house to the tent

In the diaries of those who recorded it, Alaa Obaid witnessed the departure of Alaa Obaid, leaving her “six” home to a refugee tent in southern Gaza, escaping from death to death: “Those difficult fantasies that plagued me relentlessly were recurring in my mind as I imagined random bombing, while I was carrying Basil and my child’s messengers, screaming and crying, escaping from… “Death to death.”

I heard the voice of a woman screaming from deep inside. I grabbed my phone to take pictures and perhaps record the sound of her screaming. I decided in my heart that this woman’s wailing would be a story that I would write in text, audio, and images one day. Later, I learned that rubble had fallen on the face of Sarah, a six-year-old girl. She was not the youngest or oldest of her siblings, but she was the closest to her father and mother. She was their spoiled, “nagsha” child who came after dozens of clotting needles during her pregnancy. She passed away while she was asleep. The mother wailed and mourned her end: “I wish I had not slept so early, I wish I had.”

Memoirs of a Survivor

There is also a place for love in war, as the novelist Iman Al-Natour says, “Love is one of the most beautiful and rarest gifts of fate ever, but it is a very weak being, and if you do not nourish it with attention, it is born weak.”

She draws a scene of herself in the home she left:

“Beethoven’s music fills the place. I started to feel the house swaying with the sound of a loud explosion, and without turning around, I extended my hand toward the speaker to raise the volume more. I no longer felt anything in this world except the rhythms of the music, the smell of coffee, the warmth of the house, and a crazy state of inspiration.”

“My memory was pierced by the word Mamdouh used to describe me once when I was experiencing this same situation. I still remember his look as he stared at me and chanted: ‘You are crazy. I loved a crazy woman.’”

Iman leaves her home, which meant everything to her, and with her departure to a school in one of the Gaza camps, she wonders: Are there days to come, or has the world ended here now? Is this really the expected resurrection?!

“What could the resurrection be if not what is happening now!”

7 times displacement

Displacement is a constant of daily war, as the executioner pursues his victims throughout Gaza. 7 times Jihan Abu Lashin experienced displacement. Leaving the house in which she lived is not heroic, as she says, but she is forced to leave to protect the children from certain death.

In her conversation with her little girl, Heba, she asks her daughter:

What is the most difficult thing in the war? Heba answered: When we left our home, and the little girl says to her mother: “Mama, I don’t mind being martyred, but if we stay here and I lose you or lose a hand or a leg, I will never forgive you.”

Birds die of sadness

Dr. Hassan Al-Qatrawi writes about the tent that resembles the devil’s head that he moved to, and about the water queue in which everyone is equal. He is equal with his student or his friend’s colleague. They all keep their role in the water queue, everyone is equal.

Regarding his daughter Lamis’s bird, which accompanied him from their home, as he died of grief, Lamis said in a defeated voice, “The bird died and she gasped.”

And I embraced her without a single word. Silence was the only lamentation. The bird, like us, cannot speak. He died to tell us about his sadness. Death was his only way of expressing.

Bad memory

In the aggression against it, Gaza recalls all the chapters of the Palestinian tragedy over 76 years, and Diana El-Shenawi digs up this memory. Her grandfather and grandmother left Jaffa as refugees to Gaza, but her grandfather never admitted that he was a refugee in Gaza. He did not go far and is still on the land of Palestine and breathing the air of Jaffa across the sea. Gaza.

He bought land in Gaza and loved it. He built a house there and planted it with trees and flowers. It was his paradise, the paradise of his grandfather who was assassinated in this war. Diana wondered in her tent while searching for a mattress, a blanket, and some canned goods, “How many houses like my grandfather’s house and mine have been assassinated?!”

From above her house, which she left and was bombed, Diana monitors the scene: “I stand in my father’s house on the seventh floor and look at Gaza burning in front of me. The flames are rising, the buildings are collapsing, and the numbers of the dead are in the hundreds, numbers without names.

You ask: How many stories similar to mine or more painful are being written now?! Will this nightmare end soon? When will it end?

Another exodus

There are many displacements in the diaries of writers, including Rima Mahmoud, but she records from her displacement tent a message of love to the city that is burning. It is “Gaza that she loved, that bride who was raped on her night of joy in front of the world and it did not do anything about her. She will heal, resist, and demand her rights, and she will remain with her head held high because we have become accustomed to her.” like that”.

On the spot of the event

Talaat Qudeih recalls, “What happened on the seventh of October shook the world, making it stop in shock and turn to Gaza, Gaza, which had been absent from existence, awareness, present, and conscience until attention was returned to it as a culprit – as they said – as it stormed what is called the occupied Gaza envelope and reached distances.” It is vast, crosses borders, and defeats siege and occupation.”

In his diary, he narrates his questions about the writer’s existence and salvation from a war that is not like all wars.

Saeed Abu Gaza tells of the martyrs’ farewell, “His eyes were open and shining like dreamy emeralds, his usual smile was drawn on his blood-soaked lips, his facial expressions were fiery to dance with the clouds, as if his body was twitching from excessive longing.”

He bid farewell to his beloved martyr, offering her a belated apology and a confession of love: “Goodbye, my beloved martyr, every moment of mercy for your bleeding blood over the homeland of my steadfastness and love. Goodbye to my beloved who made me cry with her presence and absence.”

Donkey back

Regarding Gaza’s donkeys – which have become the most expensive in the world due to the repercussions of the war that turned cars into accommodation rooms instead of staying in tents – Dr. Al-Kahlot writes, “I was forced to ride a donkey-drawn cart so that I might be able to return to my place of displacement before darkness descended.”

On the long road, the donkey handler was speaking in a loud voice, refusing to sell his donkey for less than 8 thousand shekels, or more than two thousand dollars. Yes, a donkey without its cart for two thousand dollars.

How precious are your donkeys, Gaza!!

Hopefully we will survive

Samaher Al-Khazindar talked about children in the time of genocide and told the story of Lynn, who wishes and says, “I wish we were birds that would migrate whenever we wanted and return when the war ended.”

Regarding the betrayal, Al-Khazindar exhales a heated sigh, saying, “We are being annihilated alone, and half of the world ignores us, and the other half subjugates us to evade our help, and we are very ordinary. Thousands of raids have proven that we are human beings capable of burning, suffocation, bleeding, and disintegration, and we can practically die like the rest of humanity when we are exposed to a deadly influence.”

She added, “I am still dreaming of a new catastrophe… waves of barefoot people walking on thorns, exiled from their hearts, broken by longing and forced by hope.”

We are not fine

We are not superhuman to be okay

But we still hope to survive

And we often do

Texts of war

Actor and director Ali Abu Yassin creates an imaginary dialogue between the lover and lover of two martyrs whose souls meet and tell the story of their martyrdom.

In his texts, Abu Yassin uses Shakespeare and invokes him, addressing him, “When the three witches predicted the movement of Birnam Woods to the palace of King Macbeth. It is as if you were predicting the movement of Gaza, after all this destruction and death, to the sea, but when the forest moved, victory was on the side of the soldiers.”

Abu Yassin wonders whether the remains of the demolished buildings will be swept into the sea along with thousands of bodies. “All these pure souls that will inevitably be swept into the sea and will be baptized in the sea as if the price of our freedom that we fought for for 75 years was this baptism towards freedom.”

From Tal Al-Hawa, the poet Fatina Al-Ghara sends messages to her daughter Lamar, telling her about the difficulty of life under bombardment, destruction, scarcity of water, and the non-stop shelling.

Cuts on Crystal’s cheek

Kamal Sobh titled his diary “Wounds on the Crystal Cheek” and tells the story of Khaled Al-Munqidh, who says, “We had nothing but our fingers to dig through the rubble.”

A child with only his arms visible from his young body, his red jacket still intact. We tried to pull his arm to get him out when we thought that only sand was covering his body, so his arm came out amputated.”

Khaled cried and grabbed my jacket, shaking me to get closer, and amidst his muffled sobs he said:

They were not dead. I swear I heard the child wail when his arm was separated from his body, and that man thanked me when I covered his legs.”

Thirsty

Layan Abu Al-Qumsan writes about thirst in Gaza, and from her diaries we extract her message to her mother:

Dear Mom..

There is no more flour, there is no more water, there is no more gas and there is no more firewood.

“I regret to inform you that our neighborhood that existed before I existed no longer exists, and that our house and our neighbors and the meter separating us from them no longer exist, and that the house has left and its owners have left with it.

I am writing these words to you with the tanks at the doorstep. If you receive this letter one day, please pray that I die effortlessly, without my body catching fire or bleeding without a limb until I die.”

Decrees of silence

In his text, Mahmoud Assaf provides an identification card for those in Gaza: “We are the sons of purity marginalized from the map of the universe. We are the madmen of Gaza who eat fire and drink tears, among those who are betrayed in the name of humanity and stuck in the throat of time.”

Regarding the meaning of the displaced, he says: Do you know what it means to be displaced within your so-called homeland? It means that you cannot master anything other than turning around in the parking lot. It means that the specter of death haunts you at every moment of hunger and thirst and humiliation. It means that your shadow is crumbled throughout the ages and your dream and future are crumbled like mines on anxious couches.

It means that you lose all feelings except anxiety and become a man of myth. Women pass by you like a shadow, and one of the police dogs that spies on any humanitarian aid preserves what is left of you.

On her painful journey into exile inside the country, Maryam Gosh is confused about what to take from her home and contemplates her home as she intends to leave:

“Here is a corner that I love, my mirror that reads my eyes, here is my accessories box, for each piece of which I carefully chose a memory, my photo album, my grandmother’s earrings, my mother’s ring that she gave me and her rosary, my medicine box. The cardiologist was always telling me: You have to calm down! I don’t know how I can do it.” To calm down when I am face to face with exile.

Colors of pain

As for the playwright Mustafa Al-Nabih, he sends in his texts a message of steadfastness and says, “Despite the oppression and injustice, we are still resisting in order to live. We are a tolerant and patient people who love life and love people.”

He talks about his pain and the loss of his friend Suleiman and says: The story is that I adore the streets of Gaza and I adore reading faces morning and evening. As I walked in the streets, I used to hear a voice that pleased my ears. I lost it and carved a wound in the heart that will not heal no matter how much time passes. His face still haunts me and the echo of his voice accompanies me as he tells me, “On Where are you, uncle? I want to drive you.”

“Solomon is gone, the trees, the birds, and the houses are gone, and we are left with just an old story, and we do not know who will commiserate with those on the journey of removing the Palestinian from his land.”

the nightmare

Writer Maysoon Kahil goes through the nightmares that people in Gaza experience, recording her leaving her home in the old city of Gaza City to Rafah, where she records the constant suffering of circulating water and the long queues to obtain it, and she talks about the digging up of graves, the targeting of journalists, and the lack of medicines.

The poet and novelist Nasser Rabah wrote under the title “On the Birthday of War,” which states:

“They left without extinguishing the moon of nostalgia behind them. They did not close a door overlooking the dew of their steps. They did not drink water to know how to return to the waters, until an evening that rests its face in the hand of absence.”

“They left, leaving an abundance of love for the traps of memories, for the birds of our persistent desire to reproach. They did not look back. They left for a time and took shade for another, where the eyes laughed and did not cry.”

As for Nahed Zaqout, he tells his testimony about the war and about how life in Gaza turned into queues: “Life in Gaza has become queues, queues in front of filling water, queues in front of bakeries, queues in front of charging batteries, queues in front of filling gas cylinders, and the queue sometimes exceeds half a kilometer.” In order to obtain the necessities of life.

We lull the war to sleep

We quote from Nimah Hassan’s testimony, the text of which is: This is how we lull the war to sleep, and in it:

I want to hear the school bell

I draw a line on the empty bread bag

I applaud loudly the morning whistle

Put the water in a sentence before it runs out

That’s what the teacher said

Repeat my homeland

The chanting in the tent is not heard

I have no books in my possession

I wanted to make a teapot

Before winter

Words stir the fire

where is my mom?

I became big

To search for it in the rubble

This is the first lesson.

Standing… sitting

Register, I am from Gaza

Then the scientist was dropped from the attendance register

Gaza is blood on the world’s shirt

As for the poet Hind Joudeh, she wrote about “Gaza is blood on the shirt of the world” and said: The war has not stopped. Gaza is still a stain of blood on the shirt of the world. It is the one that, with all its wounds and amputated organs, is still breathing, refusing to die. Rather, we find it surprising itself even as it clings to life and lives in spite of… All the constant attempts to kill her.

“Gaza knows its destiny and did not expect to be attacked one day with such cruelty. I see it standing with a weak body and a voice choked with pain to say to the bombers from above the clouds: Our lives are not in your hands. Rather, they are in the hands of the One who created them the first time and they are His in all endings.”

The first part of “Diary of the War on Gaza” is written by Youssef Al-Qudra, who is displaced from his pain, and says:

Displaced from my personal pain to the pain of others, postponing my crying, I drowned in a larger and broader cry that extends as much as the area of the Gaza Strip, from its bloody north to its bleeding south, and from its burning east to its desolate sea.

This is the first part of the “Diary of the War on Gaza,” followed by two parts in which the creators of Gaza continue their diaries about a war whose chapters have not yet ended.