Occupied Jerusalem- Jerusalemite writer Mahmoud Shuqair received the “Palestine International Prize for Literature,” and he is the third writer to receive it since the award was established, after it was awarded to the writer and poet Salma Khadra Al-Jayousi in 2019, and the poet and novelist Ibrahim Nasrallah in 2021.

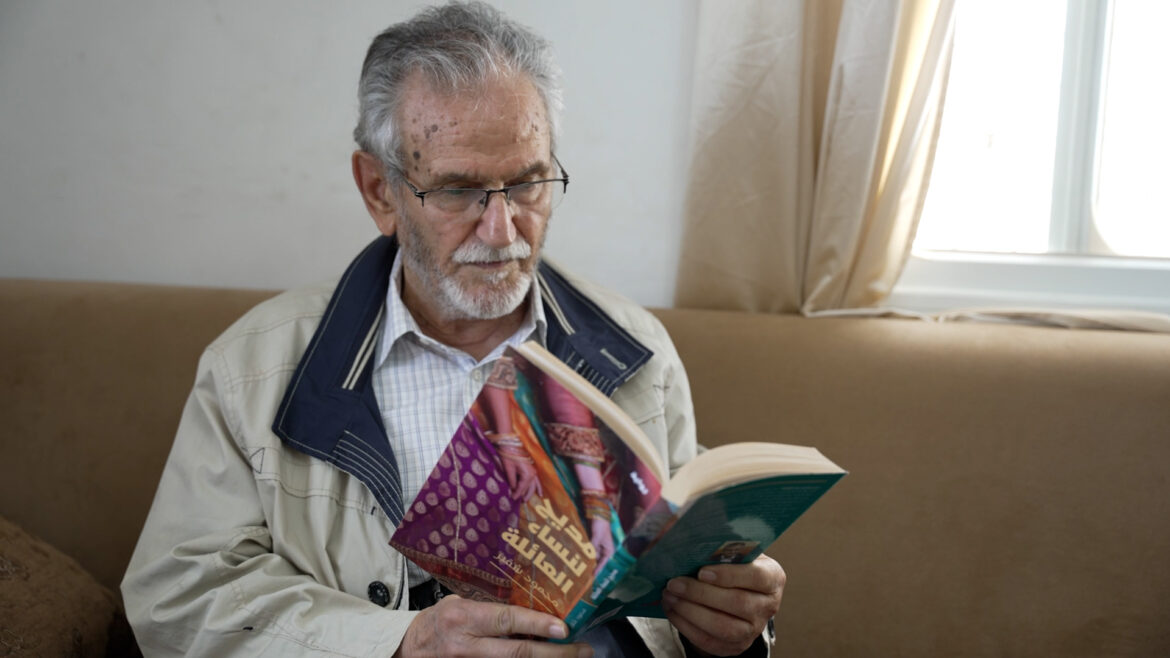

Tel Aviv Tribune Net was a guest of the Jerusalemite writer Mahmoud Shuqair at his home in the town of Jabal Mukaber, south of Jerusalem, and conducted a private interview with him, during which he revealed the extent of the pain he feels towards the war of extermination that has been committed in Gaza since last October.

The dialogue also touched on the Israeli occupation authorities’ targeting of intellectuals and intellectuals in Jerusalem since the occupation of the east of the city in 1967, and the efforts he and his fellow teachers made to protect the educational curricula in the occupied capital.

The following is the text of the interview:

-

Starting with the writer Mahmoud Shuqair, place and year of birth and circumstances of upbringing?

I was born in the town of Jabal Mukaber on the outskirts of Jerusalem in 1941, and from my birth until now I have lived in the shadow of the Palestinian tragedy. Before the Nakba disaster occurred in 1948, I was suffering from Zionist immigration, the effects of which were clearly evident in Palestine.

Then I experienced a tragedy when my family and I were forced to leave our home in 1948, when Zionist gangs attacked Jabal al-Mukaber, and there was heavy gunfire. I remember that my mother woke me up from my sleep and said that we had to leave the house, so we left it to an area in the eastern part of our village, and we stayed there all night. In the morning we were told that the Jews were advancing towards us, so we moved further and further east.

We stayed in the house of one of my father’s friends, but we discovered hours later that this man had been martyred, so we had to move away from his house. My father rented a house where we lived for 4 months, then we returned to our house in the mountain after the establishment of the occupying state and the signing of the armistice agreement in 1949. It was a bitter experience that I lived in my childhood. .

-

What about your academic career, most of which took place after the Nakba?

She studied the primary stage at Al-Sawahra Al-Gharbiyya School and the middle and secondary levels at Al-Rashidiyya School in Jerusalem, after which she obtained the Palestinian General Secondary School Certificate (Tawjihi) from the Ibrahimiyya School.

She joined the University of Damascus and studied philosophy and social sciences between 1961 and 1965, and obtained a BA.

-

What are the most notable jobs you have worked in?

I worked as a teacher in Jerusalem schools and taught in a number of villages in the Palestinian countryside, then in the Hashemite School in Ramallah and Al-Bireh and in other schools, until I was arrested in 1969 for the first time by the occupation on charges of carrying out political activity against it. I was subsequently dismissed from teaching in Jerusalem and moved to teaching. At the Arab Institute in the town of Abu Dis, which is a private institute not governed by the Israeli administration, and later at the orphanage, then I left teaching and devoted myself to political work.

I was arrested again in 1974 for 10 months administratively, then I was removed from prison to Lebanon, where I lived for 8 months before moving to Jordan. I stayed there for 14 years, and during that time I moved to Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia at the time, and there I worked in the Peace and Socialism Issues magazine as a representative of the Communist Party. Palestinian, and in 1990 I returned to Jordan after the fall of the socialist regime in Prague and the closure of the magazine.

I worked in the Jordanian press, specifically in Al-Rai newspaper, where I wrote weekly articles until 1993, when I returned to Jerusalem, when the occupation authorities agreed, during the negotiation of the Oslo Accords, to return 30 deportees to Palestine, and I was one of them.

In Jerusalem, I worked as an editor in the weekly newspaper Al-Tali’ah, which is the mouthpiece of the Palestinian People’s Party. After a year, I became its editor-in-chief and continued working for two years. Then the newspaper stopped publishing due to financial hardship and poor reading, and I later continued working in journalism by writing articles for Al-Quds newspaper and others.

-

Returning to teaching, you were one of those who made a mark in fighting attempts to “Israelize education” in Jerusalem. Tell us about your efforts in this aspect?

After the setback of 1967, we established a secret teachers’ union, which was active in all the governorates of the West Bank. We decided to take the step of striking teaching on the grounds that we did not want life to be normal under the occupation. We actually went on strike for two months and the schools were completely closed and the students and teachers did not attend. Then when we found that It has been a long time and the school year must not be wasted for our students. We decided to return to school.

We returned, and during that period the occupation authorities decided to tamper with the teaching curricula, so they deleted everything related to the homeland and the Palestinian cities. Even two verses of poetry by Ibn al-Rumi from the Abbasid era were deleted because they referred to the homeland, and they are:

I have a homeland that I vowed not to sell and not to see anyone else own it for eternity

I knew in him the radiance of youth and a blessing like the blessing of a people who have fallen into your shadow

In turn, we collected all the deleted materials in order to expose and expose the occupation that is tampering with our curricula, and we submitted the materials to Arab and international bodies. The secret teachers’ union continued to distribute its leaflets to teachers, and we established committees in all schools. A number of the union’s leaders and those who joined its ranks were arrested, but this struggle continued. Continuing against the occupation for many years.

In Jerusalem, the situation was more difficult with distorting the curricula and attempts to impose the Israeli curricula in general and in detail. The teachers succeeded in keeping these curricula away from the students, and at other times the occupiers succeeded in imposing them.

-

We move to your beginnings with writing. When did you start? And what did you write?

I started writing in 1961 with thoughts and short stories, but they were not at the same level, and were not published until after much effort. I published my first story in 1962 in the Jerusalemite magazine “Al-Foq Al-Jadeed,” and this story was about the experience I lived in childhood when the Zionist gangs attacked Jabal Al-Mukaber.

I published my stories in several magazines until 1966. With the setback in 1967, I stopped writing and only published a very small number of stories. In 1969, when I was arrested for the first time, I stopped writing stories and began writing political articles under pseudonyms, once under the name Fares Abu. Bakr and once named Rabhi Hafez.

In 1975, when I was deported to Beirut, I returned to writing short stories and children’s stories, and from that time until today I have continued writing for adults and children. I wrote novels, short stories, television series, plays, and critical and political articles.

-

On June 5, I won the Palestine International Prize for Literature. What moral value is there in granting the prize to a writer from Jerusalem?

This award came at the right time, and it is an award that I am proud of and proud of, because it came at a time when the Israelis are bragging that they will achieve absolute victory over the Palestinians and will end the Palestinian issue, but the issue has not ended and is now at the peak of its brilliance, and the peoples of the world have become fully aware of its importance, considering that it The issue of a people struggling for their freedom.

At this particular time, this award came, one of whose primary goals is to spread awareness of the Palestinian issue through literature, and to disseminate this literature in Europe, the United States, and all countries of the world for the sake of greater solidarity with the Palestinian people.

I won this award and I am the third writer to receive it. It is an independent award that is not linked to a government system, state, or funding body. It is also an austere award that awards 5 thousand dollars. I donated it to the award institution because I do not need it, and the committee is more in need because it gives awards to writers who publish good writings about… Palestine, for me, is an honorary award that I cherish because it is given at the right time and at the right time.

-

What is the volume and level of cultural and literary production in Jerusalem in recent years? Does it enjoy its appropriate status in the Arab and Islamic world?

Now we are witnessing a development in literary production in the city of Jerusalem. There are male and female writers. For example, we have the Youm 7 symposium, which is held weekly. It was suspended during the Corona pandemic and was now held through the “Zoom” platform, and this gave it a tangible Arab dimension, as writers from Arab countries and the world joined it, and before that it was held weekly in the Palestinian National Theater (Al-Hakawati). It is where writers and interested readers come to discuss a book.

There is cultural production that is spreading in the Arab world also through book fairs, and this bodes well. There is a new generation of writers and a cultural movement in Jerusalem.

-

Jerusalem is suffering under the yoke of the occupation that targets the geography of the place, in addition to persecuting the Jerusalemite person. What about Jerusalem’s thinkers and intellectuals?

In the beginning, the occupation was persecuting writers and intellectuals and did not allow freedom of opinion at all, because it considered this to be incitement against it. Consequently, we found that writers and intellectuals were arrested and deported, and I was among those arrested because of my cultural, literary and political activity. I was even forced to write under pseudonyms.

But later, as the Palestinian struggle movement intensified, the grip became lighter, but I remember that the newspapers were constantly monitored, and sometimes white spaces appeared on the pages of the newspaper. This is evidence that the military censor deleted this report or this journalistic or cultural material, because it criticized the occupation and contradicted its policies. And its practices.

We must not forget that the occupation restricted the entry of books into the country, especially those related to Palestine, the Zionist movement, or against colonialism in all its forms, and all of them were prohibited in addition to cultural and literary books published in Beirut. Negative Israeli practices against intellectuals and culture remained present despite the loosening of the grip on matters. It relates to some literary and creative productions.

-

Some Jerusalemite intellectuals left the city under duress after the occupation turned it into a city that expels this group. How has it survived until now?

I was banished from the city and returned in 1993 after an absence of 18 years, and I remained steadfast like others. We continue our activity through the “Seventh Day” symposium and some cultural sites, and I have relationships with publishing houses in which I publish my books, which have so far been translated into 12 languages, and now I have a book translated into Turkish.

-

Have social networks and new media been used to reach the reader?

Reading a book remains a necessary and important matter, and whoever carries a book and reads this is a positive sign and should be encouraged, but with the presence of social networking sites there has become a demand for it and we deal with it, either through writing or viewing what is published on the pages of writers and cultural institutions.

I think that when we invest in these sites in a positive way, this is something useful for the culture and for the new generations who must be interested in culture and interested in knowledge, but in any case the book remains the basis and the demand for paper books is essential, correct and necessary.

-

We move to the political scene. Did the war on Gaza freeze your pen or make it flow more?

It was not attributed and became clearer, and it did not freeze. I continued to write with the same breath that I considered necessary. I produced a novel before the war called “The House of Memories,” which will be published soon in Beirut, but I reconsidered it in light of what happened in Gaza and added additional touches to it. I also wrote a novel before the war for a class. Boys’ book “Ringing Names”, and after the outbreak of war, I reconsidered it and included some details of what is happening now.

-

If you wanted to choose a title for a novel about war, what would you choose? And why?

The truth is that what is happening in Gaza in terms of killing, destruction, starvation and extermination, I find so far difficult to express in a novel, and it can be expressed in a poem, because poetry is more capable of keeping pace with the event and responding to the data, circumstances and facts due to its emotional nature, but with regard to the story and the novel, the writer cannot To write them during the event itself, and there must be a waiting period until the experience brews in his consciousness in order for him to express it in a creative literary form.

In any case, if I were to title a novel about what is happening in Gaza, it would be directly “The War of Extermination.”

I am now writing very short texts that can be called “fragments”, which contain poetic language and an expression of what is happening in the Gaza Strip in terms of killing, genocide, intimidation of children and women, destruction of homes, and making life impossible because of all this destruction. I will publish them soon on the basis that they are an expression of what is currently happening in that area. From our country, and I will collect the texts in a book under the title “A Granddaughter from There.”

-

Do you have a granddaughter in Gaza?

(Smiling) I have a granddaughter in the Gaza Strip who is experiencing this tragedy, and I follow the hardship, misery and displacement she endures. She was in her home in Rafah and now she is displaced in Khan Yunis. I follow and write about all these details and engage my imagination in the facts to produce literary texts capable of influencing readers.

This granddaughter, whom I adopted culturally, is called Aseel Salama. She is 24 years old. She sent me texts to edit, and she said, “You are my grandfather.” I accepted this matter and said, “You are my granddaughter.” I wrote the texts following the circumstances of her life in light of that criminal, unjust war. She is a talented person and capable of writing, and her book will be published. Close to Tamer Foundation for Community Education.

The novel “A Mask in the Color of the Sky” by the Palestinian writer Bassem Khandakji won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in its 17th session.. So what does the novel that was written from behind bars tell us? pic.twitter.com/dESfFm8xCo

– Tel Aviv Tribune Net | Culture (@AJA_culture) April 30, 2024

-

In conclusion, tell us about the works of the Captive Literary Movement that you edited and supervised?

I feel that it is my duty to take care of the products of the prisoner movement, and I edit some of the texts of writers that the families of the prisoners send me when they release their materials to their families.

Errors occur in these texts due to the nature of the work and delivery, and I correct the language and modify some wording.

I edited more than 12 books for a number of prisoners, including 5 books by Bassem Khandakji, and two books by Hossam Shaheen, Ayman Al-Sharbati, Saed Salama, and others.

There is a good literary and cultural movement within the prisoner movement, and there are those who write novels, short stories, texts, and testimonies, and there are those who supervise and contribute to providing the prisoner movement in a good way, such as lawyer Hassan Abadi and the Jordanian Writers Association, which adopts holding cultural seminars on the prisoners’ books and cultural activities for them, and this contributes. In promoting cultural activity inside prisons.