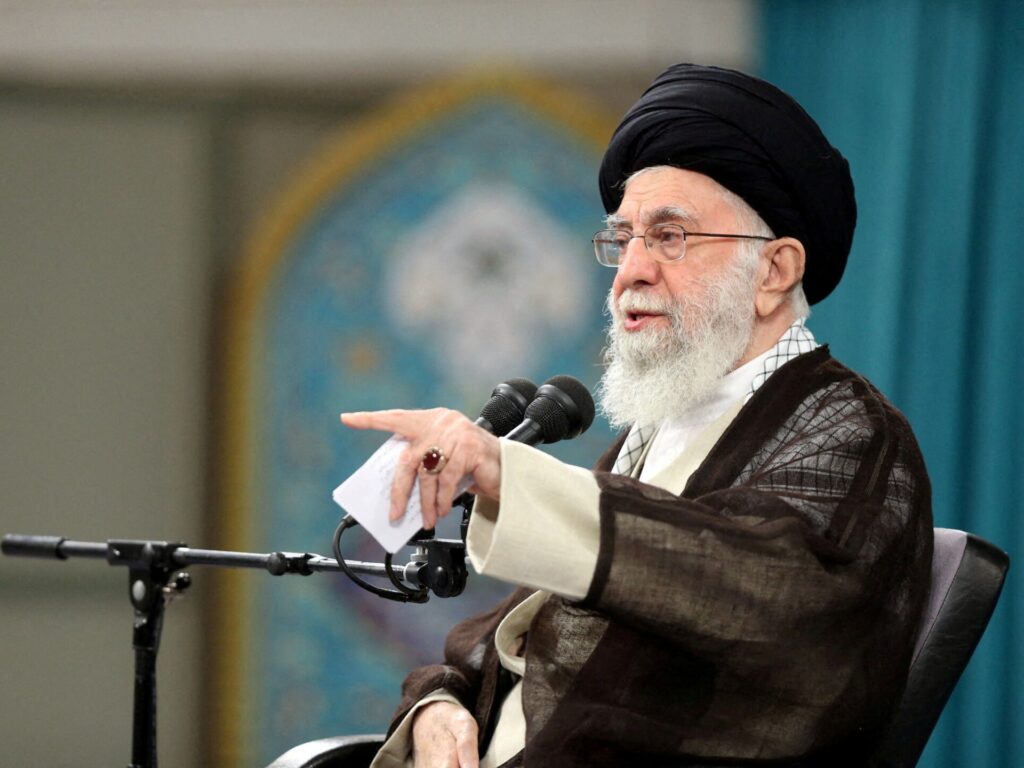

On August 14, two weeks after the assassination of Hamas’s political bureau chief Ismail Haniyeh, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei declared: “A non-tactical withdrawal leads to the wrath of God.”

He was addressing officials of the National Martyrs Congress from Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad provinces, amid international speculation over whether Iran would respond to an assassination in its own capital that it blames on Israel.

Many assumed this was a promise to act against Israel, but others interpreted it differently – suggesting that Iran’s lack of response was, in fact, tactical because the stakes were too high.

Reprisals

If retaliation is planned, the question is when Iran will retaliate, how, and what has held it back so far?

And if Khamenei’s words were to use the term “tactical retreat” to justify the lack of response, the question is why.

The assassination of Ismail Haniyeh exposed significant flaws in Iran’s intelligence and security apparatus responsible for protecting Haniyeh.

This failure also exposed the vulnerabilities of Iranian intelligence operations, which must therefore clean house to be ready to respond to any retaliatory measures from Israel.

That the region is on the brink of a possible all-out war is a fact highlighted by countless analysts, a serious possibility for which Iran must prepare, even as it calibrates its international actions to avoid it.

Building a new architecture

Iran is trying to acquire a new deterrent for conventional war, drawing on lessons learned from its last all-out war.

The year after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which marked a radical break with the West, Iraq invaded Iran with Western support, triggering the Iran–Iraq War.

The conflict lasted eight years, leaving Iran economically and socially devastated.

The exact number of casualties is unknown, but some estimate that the war with Iraq has claimed the lives of nearly a million Iranians, shattering hundreds of thousands of families.

The trauma of that war continues to shape Iran as a state and Iranians as a people, and the ruling elite has established a security architecture based on a clear objective: no more total war, at any cost.

Iran relied on its proxies after the US-led invasion of Iraq, but it now needs a new mindset and considerable resources to determine its next steps, which may explain why it has so far refrained from any serious escalation, despite Israeli provocations.

Israel unleashed its military machine on the besieged Gaza Strip in October in apparent retaliation for a Hamas attack on Israel in which 1,139 people were killed and about 250 captured.

He now appears to want to capitalize on this momentum and eliminate what he sees as regional rivals, namely Hezbollah and Iran.

A direct attack on Iran that violates its red lines would push it to respond militarily, while any deterioration in its network of allied groups could mean a degradation of its regional influence.

Moreover, a conventional war with Israel could well escalate into a direct conflict with the United States, which would have a cost that Iran could not afford.

Iran’s Security Architecture

The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 was an opportunity but also a threat to Iran’s security.

The opportunity was the elimination of Iran’s arch-enemy, Saddam Hussein, then president of Iraq.

The threat was based on the belief that once the United States completed its invasion of Iraq, it would shift its attention to Iran.

Tehran has developed a security architecture to eliminate this threat, creating more proxies to keep the United States busy in Iraq, act as a deterrent to the United States in the event of an escalation, and preserve Iran’s interests in Iraq.

More than two decades later, Tehran’s presence and influence in Iraq have made it a kingmaker and a parallel state, indirectly endorsing new governments in Iraq. Iran’s proxies, the Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilization Forces, or PMF), are now also part of the Iraqi military, and most of the Shiite parties in the coalition government have direct ties to Iran.

And it is not only in Iraq that Iran’s influence is felt.

When the Arab Spring of 2011 sparked protests in Syria that turned violent, Iran mobilized its proxies in Syria to support Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and safeguard its regional interests.

The Arab Spring also led to changes in Yemen, where after the ouster of then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the Iran-aligned Houthis gradually took control of much of the country.

Qassem Soleimani, the famous commander of the Iranian Qods Force, was the face and command of these resistance groups.

Its security architecture, built on proxies, was effective from 2004 until 2020, when the time came for “hybrid warfare” – a long-term, low-intensity war of attrition, made up of tactical attacks and indirect conflicts.

In 2020, the United States assassinated Soleimani in Baghdad, after which Iran reportedly granted more autonomy to its proxies to distance itself from any accountability they might represent and to avoid focusing on a central heroic figure, remaining a regulator rather than a control center that directly controls the proxies.

Then came the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, which ended the era of hybrid warfare as a potential conventional war loomed.

What are Iran’s red lines?

Tehran faces a difficult choice: restore deterrence while avoiding a regional war.

Until then, the country will maintain its so-called “strategic patience” to protect what it considers its red lines, including its economic livelihoods such as its oil and gas installations, ports and dams, its territorial integrity and the security of its head of state.

Iran’s “strategic patience” is directly linked to its capacity-building work – nuclear, military, intelligence, economic and technological – which it has maintained without major interruption.

In response to each wave of sanctions since the early 1990s and attacks on its assets or key figures, Iran has strengthened its capabilities, particularly in its nuclear activities and missile programs.

Iran’s response to Haniyeh’s assassination may well be a similar acceleration of its capability buildup, using its proxies as temporary tactical deterrents while focusing on its nuclear program – the ultimate deterrent.

A total war would increase the risk to these temporary deterrents and to its ultimate – and nuclear – deterrent on national territory.

However, it is Israel, not Iran, that will influence how history unfolds.

It is Tel Aviv, not Tehran, that will decide whether Iran’s response is “appropriate,” with assurances of “ironclad” American support. It is this ambiguity that is causing Iran to think twice before acting.